Editorial by Milo Schield:

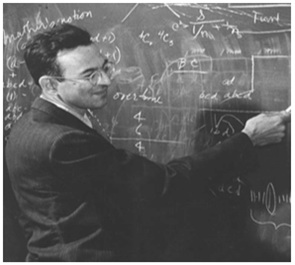

- Jerome Cornfield (Jerry: 1912-1979) is almost forgotten in the field of statistics. His Wikipedia entry is minimal. He was not included in the 2001 ISI volume “Statisticians of the Centuries” which included 103 leading statisticians. See Google Docs. As of 2017, he wasn't listed in the RSS Timeline of leading statisticians. [On 11/24/2018, I recommended he be included.]

- I consider Jerome Cornfield to be one of the most important leaders in the history of statistics. In addition to the Cornfield condition, he created several measures of association including Relative Risk and the Odds ratio. — Schield

- “Cornfield's minimum effect size is one of the greatest contributions of statistics to human knowledge alongside the Central limit theorem and Fisher's use of random assignment to statistically control for pre-existing confounders.” “To change the future, we need to go back to when Jerome Cornfield argued that smoking caused cancer.” “Our unwillingness to talk about observational causation, confounding and strength of evidence is arguably the primary reason our students' see little value in the introductory statistics normally taught in Stat 101.” “We need to teach multivariate statistics, confounding and the Cornfield conditions so students will appreciate statistics.” — Schield (2018)

- “Cornfield developed an inequality linking the observed risk ratio to the prevalence of the omitted variable...” “Cornfield's inequality was the first formal method of sensitivity analysis in observational studies or non-randomized experiments.” — Gastwirth, Krieger and Rosenbaum (2000): Cornfield's Inequality in the Encyclopedia of Epidemiological Methods, p 262-265.

- “Cornfield et al. deduced the minimum effect size necessary for a potential confounder to explain an observed association assuming the association is totally spurious.” “Cornfield's minimum effect size is as important to observational studies as is the use of randomized assignment to experimental studies. No longer could one refute an ostensive causal association by simply asserting that some new factor (such as a genetic factor) might be the true cause. Now one had to argue that the relative prevalence of this potentially confounding factor was greater than the relative risk for the ostensive cause. The higher the relative risk in the observed association, the stronger the argument in favor of direct causation, and the more the burden of proof was shifted onto those arguing against causation. While there might be many confounding factors, only those exceeding certain necessary conditions could be relevant.” — Schield, 1999

- Cornfield's “minimum-effect size” argument was critical in supporting the claim that smoking caused cancer. See the 1964 Surgeon General's report. See also Hill's 1965 President's address titled “The Environment and Disease: Association or Causation?.” Note that of Hill's nine criteria, “strength” was #1. — Schield

- “This report reviews some of the more recent epidemiologic and experimental findings on the relationship of tobacco smoking to lung cancer, and discusses some criticisms directed against the conclusion that tobacco smoking, especially cigarettes, has a causal role in the increase in broncho-genic carcinoma. The magnitude of the excess lung-cancer risk among cigarette smokers is so great that the results can not be interpreted as arising from an indirect association of cigarette smoking with some other agent or characteristic, since this hypothetical agent would have to be at least as strongly associated with lung cancer as cigarette use; no such agent has been found or suggested.” — Cornfield J, Haenszel W, Hammond EC, Lilienfeld AM, Shimkin MB, Wynder EL (1959). Smoking and lung cancer: Recent evidence and a discussion of some questions. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 22 (1):173-203. TOC. Copy in 2009 Int. J. Epidemiology. Local copy

GENERAL ARTICLES BY CORNFIELD

- 1975 A Statistician's Apology. Jerome Cornfield's ASA address as the ASA President.

ARTICLES ABOUT CORNFIELD:

- 2015 Jerome Cornfield in Wikipedia (July)

- 2015 Jerome Cornfield's Bayesian approach to assessing interim results in clinical trials by JJ Schlesseman in James Lind Library.

- 2013 Jerome Cornfield: The statistician who established risk factors for lung cancer and heart disease by R. Wicklin in SAS Blog.

- 2013 Tribute to Jerome Cornfield: A Legacy in the Field of Statistics by SW Greenhouse and M. Halpern in Amstat News.

- 2013 History of Statistics at George Washington University by Gastwirth et al. P. 68 in Strength in Numbers by Agresti and Meng. TOC

- 2012 A celebratory tribute to world-renowned statistician Jerome Cornfield by Joel Greenhouse in Statistics Views

- 2010 Commentary on Cornfield (1951) by JJ Schlesselman.

-

2009 Smoking and lung cancer: causality, Cornfield and an early observational meta-analysis by Editor George Davey Smith in Int. Jrnl Epidemiology V. 38. Copy Copy2

“Perhaps one of the advantages that Cornfield had was his lack of any sustained formal training in either epidemiology or biostatistics.”

As JBS Haldane—who recently graced the ‘Reprints and Reflections’ section of the IJE—pointed out, ‘I consider it desirable that a man’s or a woman’s major research work should be on a subject in which he or she has not taken a degree. To get a degree one has to learn all the facts and theories in a somewhat parrot-like manner. One may also learn something much more important, namely how a branch of knowledge has been organised. And a piece of research directed by a good scientist should leave one with high standards of accuracy and integrity which one can transfer to other fields of science. It is rather hard to be highly original in a subject that one has learned with a view to obtaining first-class honours in an examination’. — Source

“Perhaps the growth of formal epidemiology courses over recent decades is doing a disservice to the originality of thinking in the field.”

“Cornfield’s initial degree and graduate study were in history.”- 2009 Commentary: Smoking and lung cancer: reflections on a pioneering paper by DR Cox (pg. 1192-93). [No mention of Cornfield's conditions. — Schield]

-

2009

Commentary: ‘Smoking and lung cancer’—the embryogenesis of modern epidemiology

by JP Vandenbroucke. (pg. 1193-96). “This

conclusion of the paper rests on an algebraic derivation in an appendix

and is what the paper is often remembered for nowadays. Although

conceptually simple, it represented a gigantic leap forward, and might

be seen as the starting point of all sensitivity analyses. The notion

that large relative risks can be convincing by themselves is still very

much alive. However, over the past few decades, the concept has often

been reversed, to shed doubt on ‘small relative risks’, which led to

statements that only relative risks >3 would be credible. That is not

what the original said. The paper proposed that it is difficult to think

of potential confounders to explain a 9-fold relative risk of smoking on

lung cancer incidence because a potential confounder should be even more

strongly associated with smoking. That does not mean that such

confounders cannot exist, but that it is difficult to come up with

likely candidates to explain away a large relative risk. For small

relative risks more candidate confounders can be imagined, which in turn

does not mean that the association is in fact confounded. Smaller

relative risks may need more epidemiologic evidence, from repeated

studies trying to tackle potential bias and confounding, as well as

additional evidence from other lines of research, e.g. experimental

evidence about biologic mechanisms.

Perhaps Cornfield did not only give us the odds ratio, the logistic regression and the stratification by a confounder score, but also demonstrated how to reason about epidemiologic data in the midst of a controversy—a quality that that was clearly and affectionately remembered in a series of papers dedicated to his memory.” - 2009 Commentary: Cornfield, Epidemiology and Causality by Joel B. Greenhouse. “I argue that Cornfield’s odds ratio in case-control studies, together with his necessary condition on the magnitudes of relative risk in light of confounders, were essential tools in confronting the skeptics.”

- 2009 Commentary: Cornfield on cigarette smoking and lung cancer and how to assess causality by Marcel Zwahlen. “For Cornfield and colleagues, the most difficult challenge was the argument implicating a confounding variable ‘X’. <snip> As outlined in Appendix A of their article, boundaries can be derived on how prevalent the factor ‘X’ would need to be in smokers compared with non-smokers. These boundaries were then used to argue that no one could suggest a candidate for such a characteristic ‘X’ and the odds of finding one in the future seemed very small indeed. Here, Cornfield and colleagues clearly illustrate why epidemiologists examine relative risk measures when assessing whether an observed association is likely to be causal. Furthermore, we find here an early example of explicitly and quantitatively accounting for an unobserved additional variable. The area of explicitly modelling bias mechanisms or the influence of unobserved (often called latent) variables has gained importance in epidemiology in recent years.”

- 2022 Cornfield's use of Causal Grammar. By M. Schield. Research paper.

- 2009 Epidemiologic Causation: Cornfield’s Argument for Causal Connection between Smoking and Lung Cancer by Roger Sanev. Humana Mente.

- 2005 Greenhouse, Samuel W. (2005). “Cornfield, Jerome.” Encyclopedia of Biostatistics. John Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1002/0470011815.b2a17032

- 2000 Cornfield's Inequality in the Encyclopedia of Epidemiological Methods. By Joe Gastwirth, Abba Kreiger and Paul Rosenbaum.

- 1999 Simpson's Paradox and Cornfield's Condition By Milo Schield in the ASA Proceedings of the Section on Statistical Education. Reviews the Cornfield conditions and reproduces the entire appendix of Cornfield classic response to Sir Ronald Fisher to which Fisher never replied.

- 1982 Mantel N.. Jerome Cornfield and statistical applications to laboratory research: a personal reminiscence. Biometrics 38(Suppl):l7-23.

- 1982 Greenhouse, Samuel W. (1982). “A Tribute” Biometrics 38 (Proceedings of “Current Topics in Biostatistics and Epidemiology.” A Memorial Symposium in Honor of Jerome Cornfield): 3–6. JSTOR 2529847.

- 1982 Greenhouse SW. A Tribute. Biometrics 38(Suppl):3-6. Greenhouse SW (1982b). Jerome Cornfield's contributions to epidemiology. Biometrics 38(Suppl):33-4

-

1982

Abstracts

in

Biometrics

- The contributions of Jerome Cornfield to the theory of statistics by M Zelen.

- Jerome Cornfield's contributions to epidemiology by SW Greenhouse.

- 1960 Cornfield's contribution Johns Hopkins Biostatistics History.

ABSTRACTS OF ARTICLES ABOUT CORNFIELD:

-

2012 Bayesian clinical trials in action by JJ1 Lee and CT Chu. Stat Med. 2012 Nov 10;31(25):2955-72. doi: 10.1002/sim.5404. Epub 2012 Jun 18.

Abstract: Although the frequentist paradigm has been the predominant approach to clinical trial design since the 1940s, it has several notable limitations. Advancements in computational algorithms and computer hardware have greatly enhanced the alternative Bayesian paradigm. Compared with its frequentist counterpart, the Bayesian framework has several unique advantages, and its incorporation into clinical trial design is occurring more frequently. Using an extensive literature review to assess how Bayesian methods are used in clinical trials, we find them most commonly used for dose finding, efficacy monitoring, toxicity monitoring, diagnosis/decision making, and studying pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics. The additional infrastructure required for implementing Bayesian methods in clinical trials may include specialized software programs to run the study design, simulation and analysis, and web-based applications, all of which are particularly useful for timely data entry and analysis. Trial success requires not only the development of proper tools but also timely and accurate execution of data entry, quality control, adaptive randomization, and Bayesian computation. The relative merit of the Bayesian and frequentist approaches continues to be the subject of debate in statistics. However, more evidence can be found showing the convergence of the two camps, at least at the practical level. Ultimately, better clinical trial methods lead to more efficient designs, lower sample sizes, more accurate conclusions, and better outcomes for patients enrolled in the trials. Bayesian methods offer attractive alternatives for better trials. More Bayesian trials should be designed and conducted to refine the approach and demonstrate their real benefit in action. — PubMed PMID: 22711340.PMCID: PMC3495977

-

2005 'Jerome Cornfield' by SW Greenhouse in Biostatistics. “Born in 1912 in New York City; died in 1979 in Herndon, VA. Best known for helping develop Cornfield's inequality linking the observed risk ratio to the prevalence of the omitted variable in smoking and nonsmoking groups.”

Excerpt1: “When epidemiologists began turning their attention to the study of chronic diseases, prospective cohort designs for finding causes of, or risk factors for, chronic diseases were in many instances impractical. They therefore turned to case–control or retrospective types of strategies. A problem with these designs, assuming they are well planned, is that they do not yield traditional estimates of absolute risk or relative risk. Cornfield, in 1955 at the Third Berkeley Symposium in Mathematical Statistics and Probability [4, 18], presented a derivation which demonstrated that under a rather strong assumption (but rather reasonable in the case of chronic diseases) the odds ratio or cross product ratio (in a 2×2 table) is a fairly good approximation of the relative risk. The assumption was that the incidence of the disease under study should be small.”

Excerpt2: “the question of the effect of latent, unobservable variables. Sir Ronald Fisher, in arguing against the smoking — lung cancer relationship, had offered an hypothesis that postulated the existence of some constitutional factor (latent and unobservable), e.g. genetic, that caused cancer and that was also associated with the need to smoke. Without giving the details of his argument here, Cornfield demonstrated that if cigarette smokers are shown to have nine times the risk of nonsmokers of getting lung cancer, but that this elevated risk is due, not to cigarettes, but to some latent factor X, then the proportion of smokers having X must be larger than nine times the proportion of nonsmokers having X. Cornfield’s conclusion was that if X was a causative agent of this magnitude, then the relationship between the latent factor X and the observed agent would probably have been detected much before that of the agent and the disease. No such factor has been found.”

-

1982 The contributions of Jerome Cornfield to the theory of statistics by M. Zelen. Biometrics. 1982 Mar;38 Suppl:11-5.

Abstract: This paper is a review of the contributions of Jerome Cornfield to the theory of statistics. It discusses several highlights of his theoretical work as well as describing his philosophy relating theory to application. The three areas discussed are: linear programming, urn sampling and its generalizations to the analysis of variance, and Bayesian inference. It is not widely known that Jerome Cornfield was perhaps the first to formulate and approximately solve the linear programming problem in 1941. His formulation was made for the famous “Diet Problem.” An early publication introduced the method of indicator random variables in the context of urn sampling. This simple method allowed straightforward calculations of the low order moments for estimates arising from sampling finite populations and was later generalized to the two-way analysis of variance. The application of the urn sampling model to the analysis of variance served to illuminate how one chooses proper error terms for making tests in the analysis of variance table. Jerome Cornfield's philosophy on applications of statistics was dominated by a Bayesian outlook. His theoretical contributions in the past two decades were mainly concerned with the development of Bayesian ideas and methods. A brief survey is made of his main contributions to this area. A particularly noteworthy result was his demonstration that for the two-sample slippage problem of location, the likelihood function under a permutation setting is uninformative for the slippage parameter. However, the posterior distribution differs from the prior distribution despite the fact that the likelihood is uninformative. — Source

-

1982 Jerome Cornfield's contributions to epidemiology by SW Greenhouse. Biometrics. 1982 Mar;38 Suppl:33-45.

Abstract: This paper reviews the contributions Jerome Cornfield made to epidemiologic methodology. Section 2 discusses his development of the odds ratio obtained in a case-control study as an estimate of the relative risk of the disease under study. Section 3 presents Cornfield's introduction of the multiple logistic risk function as a smoothing function for data classified in a multi-way contingency table in order to determine the joint effects of several risk factors on the incidence of a disease. Section 4 gives a brief description of his work in the analysis of contingency tables. In Section 5, there is a summary of his views on a number of issues relating to the research, mostly case-control studies, on the relationship between smoking and lung cancer. The discussion in this section is selective and undoubtedly does not reflect all the important things he had to say on the subject. Finally, in Section 6, there is a discussion, based on only one of his papers on the subject, of some very significant thoughts on intervention studies in coronary disease. — Source

-

1982 Jerome Cornfield's contributions to the conduct of clinical trials by F. Ederer. Biometrics. 1982 Mar;38 Suppl:25-32.

Abstract: Jerome Cornfield's important contributions to the conduct of clinical trials are summarized here. They include consultative advice in the planning of many national trials, active collaboration in the conduct of many others, discussions of the role of classical and Bayesian methods of statistical inference in clinical trials, recommendations on data monitoring, contributions to the analysis of results of the University Group Diabetes Project, and efforts to assist the planning of coronary intervention trials with quantitative assessments of possible reductions in disease rates due to intervention on smoking and diet. An attempt is made to evaluate the impact of Cornfield's contributions to clinical trials. — Source

BRADFORD'S ARTICLES ON SMOKING and LUNG CANCER:

- Hill, A. Bradford (1952). The Clinical Trial. New England Journal of Medicine 247. No 4 P. 113-119.

- Hill, A. Bradford (1953). Observation and experiment. New England Journal of Medicine 248:995-1001.

- US Surgeon General's Report: Smoking causes lung cancer. Associated Press Story 1964

- Hill, A. Bradford (1965). The environment and disease: association or causation? Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine 58:295-300.

FISHER'S ARTICLES ON SMOKING and LUNG CANCER:

- Smoking — The Cancer Controversy (Some Attempts to Access the Evidence)

- Ben Christopher (2016). Why the Father of Modern Statistics Didn't Believe that Smoking Caused Cancer.

ARTICLES BY CORNFIELD:

- Cornfield, J (1951). Method of estimating comparative rates from clinical data. Applications to cancer of the lung, breast and cervix. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 1951; 11, 1269-75

- Cornfield J (1954). Statistical relationships and proof in medicine. The American Statistician 8(5):19-21.

- Cornfield J (1956). A statistical problem arising from retrospective studies. Proceedings 3rd Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics 4:135–48.

- Cornfield J (1959). Principles of research. American Journal of Mental Deficiency 64:240-252. Reprint 2012 Statistics in Medicine P1

-

Cornfield J, Haenszel W, Hammond EC, Lilienfeld AM, Shimkin MB, Wynder EL (1959). Smoking and lung cancer: Recent evidence and a discussion of some questions. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 22 (1):173-203. TOC. Copy in 2009 Int. J. Epidemiology.

Summary: “This report reviews some of the more recent epidemiologic and experimental findings on the relationship of tobacco smoking to lung cancer, and discusses some criticisms directed against the conclusion that tobacco smoking, especially cigarettes, has a causal role in the increase in broncho-genic carcinoma. The magnitude of the excess lung-cancer risk among cigarette smokers is so great that the results can not be interpreted as arising from an indirect association of cigarette smoking with some other agent or characteristic, since this hypothetical agent would have to be at least as strongly associated with lung cancer as cigarette use; no such agent has been found or suggested. The consistency of all the epidemiologic and experimental evidence also supports the conclusion of a causal relationship with cigarette smoking, while there are serious inconsistencies in reconciling the evidence with other hypotheses which have been advanced. Unquestionably there are areas where more research is necessary, and, of course, no single cause accounts for all lung cancer. The information already available, however, is sufficient for planning and activating public health measures.”

- Cornfield, Haenszel and Hammond (1960). Some aspects of retrospective studies. Journal of Chronic Diseases 11:523-534.

- Cornfield, Gordon and Smith (1961). Quantal response curves for experimentally uncontrolled variables. Bulletin of the International Statistical Institute 38: 97-115.

- Cornfield J (1962). Joint dependence of risk of coronary heart disease on serum cholesterol and systolic blood pressure: a discriminant function analysis. Federation Proceedings 21:58-61.

- Cornfield J (1966a). A Bayesian test of some classical hypotheses, with applications to sequential clinical trials. Journal of the American Statistical Association 61:577-594.

- Cornfield J (1966b). Sequential trials, sequential analysis and the likelihood principle. The American Statistician 20:18-23.

- Cornfield J, Greenhouse SW (1967). On certain aspects of sequential clinical trials. In Proceedings of the Fifth Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability, Vol. 4. (eds. Neyman and LeCam) pp. 813-829.

- Cornfield J (1969). The Bayesian outlook and its applications (with discussion). Biometrics 25:617-657.

- Cornfield J (1970a). Fixed and floating sample size trials. In Symposium on Statistical Aspects of Protocol Design. Engle RL, Jr. (Symposium Chairman). Bethesda, Maryland: Clinical Investigation Review Committee, Clinical Investigations Branch, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, pp 181-187,with discussion on pp 197-204.

- Cornfield J (1970b). The frequency theory of probability, Bayes' theorem, and sequential clinical trials. In Bayesian Statistics (eds. Donald L. Meyer, Raymond 0. Collier, Jr.) Itasca, Illinois: Peacock Publishers Inc., pp 1-28.

- Cornfield J (1970c). Discussion by J. Cornfield, B.M. Jill, D.V.Lindley, S. Geisser, and C.M. Mallows. In Bayesian Statistics (eds. Donald L. Meyer, Raymond 0. Collier, Jr.) Itasca, Illinois: Peacock Publishers Inc., pp 85-125.

- Cornfield J (1971). The University Group Diabetes Program. A further statistical analysis of the mortality findings. Journal of the American Medical Association 217:1676-1687.

- Cornfield J (1974a). Statement of Dr. Jerome Cornfield, Chairman, Department of Statistics, The George Washington University, Washington, D.C. In Subcommittee on Monopoly (1974), pp 10778-10794.

- Cornfield J (1974b). Interrogation of Holbrooke S. Seltzer, M.D. In Subcommittee on Monopoly (1974), pp 10889-10895.

- Cornfield J (1974c). Correspondence between Senator Gaylord Nelson and Neil L. Chayet, Dr. Jerome Cornfield, Dr. Christian R. Klimt, and Dr. Jeremiah Stamler. In Subcommittee on Monopoly (1974), pp 11507-11523.

- Cornfield J (1975). A statistician's apology. Journal of the American Statistical Association 70:7-14.

- Cornfield J (1976). Recent methodological contributions to clinical trials. American Journal of Epidemiology 104:408-421.

- Cornfield J (1978). Randomization by group: a formal analysis. American Journal of Epidemiology 108:100-102.

- Jerome Cornfield Papers: Historical Note. Special Collections Department, Iowa State University.

- Jerome Cornfield's Bayesian approach to assessing interim results in clin… http://www.jameslindlibrary.org/articles/jerome-comfields-bayesian-app … 10 of 13

- For a complete listing, see Jerome Cornfield's Publications.

Other Papers involving CORNFIELD or CONFOUNDING:

- 2018 Wikipedia: Confounding

- 2015 Wikipedia: Jerome Cornfield

- 2004 Jan Hajek Causation and Confounding Milo Schield: “Jan has a most-interesting mind. He spotted an unwarranted step in one of my papers. As I recall, he said he figured out how to handle packet ‘collisions’ on the early internet.”

Other AUTHORS involving CORNFIELD or CONFOUNDING:

-

Paul Rosenbaum

(Related items).

Profile

- Observational Studies. Springer Series in Statistics, New York, Springer. First edition 1995, second edition 2002.

-

Design of Observational Studies. Springer Series in Statistics, New York, Springer, 2010.

Observation and Experiment: An Introduction to Causal Inference. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2017. - From association to causation in observational studies: The role of tests of strongly ignorable treatment assignment. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 1984, 79,41-48

-

Joe Gastwirth (full list of related paper)

- Yu, B. and Gastwirth, J.L. (2003). The reverse Cornfield Inequality and its Use in the Analysis of Epidemiologic Data. Statistics in Medicine, 22, 3383-3401

- Yu, B. and Gastwirth, J.L. (2008). A Method of Assessing the Sensitivity of Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel Test to an Unobserved Confounder. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences-A, 366, 2377-2388.

Other AUTHORS involving EPIDEMIOLOGY:

- Gary Taubes: 1995 Epidemiology Faces Its Limits. Science. 1995 Jul 14;269(5221):164-9.

-

Commentaries (Science, 1995): the discipline of epidemiology

- Willett W, Greenland S, MacMahon B, Trichopoulos D, Rothman K, Thomas D, Thun M, Weiss N. Science. 1995 Sep 8;269(5229):1325-6. PMID: 7660105

- Trichopoulos D. Science. 1995 Sep 8;269(5229):1326. PMID: 7660106

- Rapp J. Science. 1995 Sep 8;269(5229):1326-7. PMID: 7660107

- Miller RW. Science. 1995 Sep 8;269(5229):1327. PMID: 7660108

- Saah AJ. Science. 1995 Sep 8;269(5229):1327. PMID: 7660109

- Gori GB. Science. 1995 Sep 8;269(5229):1327-8. PMID: 7660110

- Hertz-Picciotto I, Hatch M. (1995) Glass ceiling: bump, bump. Science. 1995 Sep 8;269(5229):1328. PMID: 7660111

- Smith AH. (1995). Depicting epidemiology. Science. 1995 Dec 15;270(5243):1743-4. PMID: 8525357